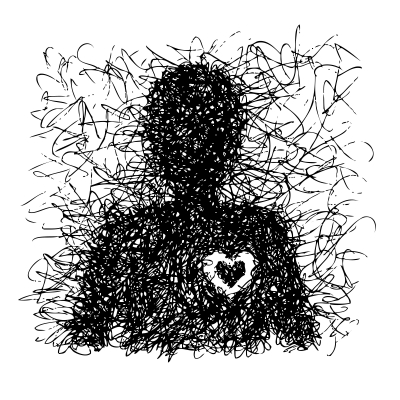

Image Simon Howden, freedigitalphotos.net

Julie eventually called the police.

To be honest I was surprised that none of the other guests had, but then really we were the last of the immediate family, I suppose everyone just assumed I would do it.

When they came they asked the usual questions, and we all sat in the ballroom and drank tea and answered them in bewilderment. No one knew anything. No one knew Uncle enough to know anything.

“He was something of an enigma you see.” Julie said. I just laughed at her.

“He wanted everybody to think he was an enigma,” I corrected her. He was just an arrogant prick I was thinking to myself. The letter my grandfather had written to him was etched into my mind. I hated that there were family secrets that my uncle had withheld from us, that he might have gone against Grandfather’s wishes on anything.

“Are you alright, do you want to head back to the city?” Julie asked me anxiously after the police had left to search the grounds.

“No, of course not. We can’t leave not knowing a thing.”

“But you look so tired, and I’m tired, it’s this place, it’s so–I don’t know…”

“You go. I can take care of things from here.”

Julie looked up at me through pink-tinged eyes.

“Are you sure?I really don’t want to abandon you here.” She was desperate to leave.

I told her to go home and she was gone that afternoon. As if taking that as their cue, most of the others abandoned ship too. In the end there was only myself, Marshall and Frank. Frank stayed as he and I went back a long way, to university, he was a friend of the family, Marshall stayed I think because my uncle owed him money. I don’t blame him one bit, but he never got a penny of it back.

We, the three of us, spent the evening discussing events in minute details. When was the last time anyone had seen or heard from Uncle? What correspondence had we had with him? What had we discovered in our searches of the house? Most of it was fruitless chat that led nowhere, I got the distinct impression that all of us knew things about my Uncle that they didn’t want to discuss with the others. Enemies? Of course he had none.

The police found nothing on the first sweep round. They said some officers would come round in the morning to continue the hunt.

“What are you looking for exactly?” Frank asked them. Marshall and I exchanged a look between ourselves and the officer he addressed shifted awkwardly.

Frank cleared his throat. “I mean, you don’t think they’ll be bodies do you?”

That night I dreamt I heard the sound again, that bellowing. I dreamt I was being hunted down by something I could never fully see. It was like a whirling mass of dark hair, sticky with blood which glinted where the moonlight struck it whenever I happened to turn to see the thing advance upon me. I ran until I stumbled, I cried out for my grandfather and I thought I could hear him shouting to me from somewhere through the mist. I called for him, but even in the dream I was still searching for my uncle. The beast was right up behind me and I felt like it would catch me at any minute, I felt myself slowing, and as I did so, it did too. It hunted my steps and drove me forwards. I looked up and saw, illuminated by a ghostly glow, the copse. The mists parted and I saw it clearly; there was a little chapel with a light in the window nestled right in its heart. But something moved and suddenly the light was extinguished. I looked again and the chapel was a ruin. I ran towards it, but it appeared to crumble away to rubble as I advanced. When I reached the copse, I saw that it was as I had always known it, nothing but straggles of overgrowth and mournful, barren trees. I turned then, and looked for the beast, but it had completely vanished. I woke, thinking I heard a howling, and could not get back to sleep.

The police found the room my uncle had been sleeping in. Frank owned up and said he had thought it was just a storage room on the ground floor, and I can’t say I blamed him. It was filled with junk. There were mops and ruined towels covered in paint; some broken cabinets and a couple of pieces of awful wall art. The bed had been almost totally obscured by boxes. Over in the corner, tucked under a mass of bed linen, they found a suitcase.

I don’t know why, but something about seeing that suitcase filled with my uncle’s possessions finally made me feel something. Perhaps I had only ever seen him as a caricature, now, gazing at the open case I saw his life encapsulated in the few things he treasured and had chosen to hide. The police showed it to me, they asked if I could identify it as belonging to my uncle. His name wasn’t on anything. There was a diary, his shaving things, a newspaper clipping from the restaurant he had owned many years ago. There was a battered copy of Hemmingway’s The Sun Also Rises, and tucked away within it, a photograph of a woman.

I shan’t go into the rest. I don’t like to think about it. There was a diary too which the police showed to me. I immediately recognised my uncle’s handwriting. How badly I wanted to get out of there! I didn’t want to read his words, but I was suddenly gripped with a desire to find him as I did, to put an end to all the mystery and the waiting. As my eyes scanned the scrawled paragraphs, brief passages about minutiae seemed to me to be obscuring something. I read on a little more and then stopped short.

“Anything in there you think relates to his disappearance?” The officer asked me, waiting.

“No, not a thing,” I lied to him. I didn’t tell him how scared my uncle must have been, to write some of those things. They would find out for themselves.

Kristen has just reminded me to check the blue bathroom on the ground floor, she thinks there might be rats. She says she can hear them scurrying about near her room and thinks they may be nesting in there. I think she’s being jumpy but I’ll check now anyway. I could leave it til tonight but I hate turning my back on that window that looks out onto the lawn. I keep thinking I can see a light in the copse…

It’s 6am. I had that dream again. Every time it’s like I feel the thing’s breath on my neck. I keep waking thinking it’s tearing me apart.

As soon as I read those final lines, I put the diary back and stepped away. They took what remained of my uncle away in that suitcase and I never saw it again. Julie kept it. I wouldn’t have it anywhere near me.

I told Frank and Marshall that it was pointless to stay. The police would do everything they could. Frank being the affable soul that he was offered to stay but I convinced him to go, Marshall packed up in a hurry, with a face like thunder. The last I saw of him was his bent frame hunched over a telephone in the reception area, speaking to someone in hushed, irritated tones. “This is all some ploy of his, I know it is,” he was saying.

I could have gone then and there, just taken my things and left. But I told the police I would stay one more night and then leave in the morning. A mad idea perhaps, perhaps I should have just left with the others. But for whatever reason, I stayed. I think it was this fading hope that my uncle would return once the police left. I kept looking out for him, listening for the door.

As I watched the others drive away I was greeted with a sunset like a bleeding wound, a red light spilling onto the grounds and a bitter wind. I made a dinner of sorts in the kitchen, and then resolved to head straight to my room, but as I turned the corner on the landing I thought I heard something, a rustling, like rats. Remembering the diary entry I followed the sounds to the blue bathroom and peered inside. The light illuminated a huge bath tub and the usual toiletries, but no rats. I was about to turn to leave when I saw, tucked down behind the bath, a pamphlet. I managed to extract it from where it lay nestled in amongst the pipes and flicked through it. It listed the history of the area, and several pages in, I saw an etching of the old copse as it had once been, complete with the little chapel. The page had been folded over at the corner, as if the reader had specifically marked that spot.

There was a brief paragraph detailing the history of the chapel and its uses, and it remarked how the site had fallen into disrepair generations ago. There was even a little legend about the place, about some goings on between the lady of the house, and a local man of the cloth. It was pretty standard fayre for the most part; the head of the house was rumoured to be involved with the occult, several servants deserted their posts due to strange noises and visions. It was all the usual stuff they put in those sorts of amateur guides, but right at the end there was something odd, about how they had found the two clandestine lovers horrifically mauled inside the chapel.

This part of the pamphlet had gotten wet and was wrinkled enough to make reading difficult. Someone had scribbled something in pen, which had bled in the damp, all I could make out were the words: “- guest”

I resolved to take the pamphlet with me to bed, and scrutinize it further. As I stood up I felt a cold chill on the back of my neck and turned around to see the window, and a light in the copse.

Without thinking I ran out to it. I was afraid and I stumbled as I ran but some vain hope made me think that it might be my uncle. That he might still be alive. I couldn’t stop thinking about that suitcase, about the fragmented life that it contained. We had never seen eye to eye but he was still my uncle, in spite of it all.

As I rushed out to meet the light I never once looked back, I could see, in my minds eye the beast from my dreams at my heels. I thought of the passage in my uncle’s diary and knew that he was haunted by a similar monster. Real or imaginary, it didn’t matter. I arrived at the ruins, panting, fog had descended and made the air painfully cold as it entered my lungs. The grass was squeaky with dew and the ground muddy underfoot, Up ahead the trees loomed, thin and miserable. I hunted for the light, I pushed my way in and trod on jutting gravestones as I did so, but I saw nothing, just the last rays of the sun going down. That was all I had seen.

I had no nightmares that night, not that I slept much. The house was eerily silent, as if it was finished with me, as if it had toyed with us all enough and was now dormant again. I closed the heavy door and locked it, wondering if I would ever return to that place. I’d persuade Julie to sell it; if uncle was really gone then it would pass to one of us, surely. In the cold light of day it seemed plausible that he had simply abandoned the place, that he had run off with that woman, Kristen, determined to leave it all behind. I told myself that as I walked towards the car. Before I could get in, something caught my eye. A man was walking towards me from the grounds, he was waving and I had to stop, frustrated, and wait for him.

“You’re his nephew aren’t you?” The man said, his accent thick, his clothes muddy. I nodded and waited for him to continue.

“Are you for the off then?” Was all he said. “Yes,” I said. “Did you know my uncle?”

He seemed to find this amusing, “Lord no. Spoke to him once maybe, that’s about it.”

I made as if to go but he stopped me.

“They won’t find him.” He raised a bushy eyebrow at me as he said it, and it made me pause.

“Why, exactly?”

“Do you want to know where he is?” He asked.

I nodded. I’ll admit I was a little afraid, but looking at the man I decided that he was too old and slight to be a murderer, so I followed him across the fields in the damp morning.

“You know the place.” He said, we were heading towards the copse.

“Yes. But the police searched in there.”

The man snorted. “Police!” He said and shook his head.

We came upon the copse, it looked a lot meeker, and smaller in daylight. Last night it had seemed so infinite, sprawling, almost alive with menace.

“He tried to get them to dig it up, all this ground, he said he wanted to build a, what do they call it? A spa. That was it. It was gonna be a small, heated shed, something like that, that’s what they told me.” The man gestured to where the sunken tombstones protruded through the grass like parts of a spine.

“A sauna for the hotel?” He nodded. “Why didn’t they? Why didn’t he build it.”

“Ah.” The man wiped his head. “Well I know why. I mean, they were local boys. But officially, they said it was because the ground wasn’t right. That it would be take too long and cost too much and your uncle didn’t want to listen to all that so he sent them away and tried to clear a lot of the rubble by himself, with the woman.”

We wandered into the heart of the copse, scattered remains of fallen masonry littered the ground under our feet.

“Not far now, though I hope I’m wrong.” The man took me to a spot, bordered by trees and stones.

“The police won’t have looked in here.” He said. I went over to him, and watched him kneel and pull back a covering of thick branches which disguised a hole in the ground, like a rabbit warren big enough for an average man to crawl through.

“Do you want to go or shall I?” He asked.

“What is it?” I didn’t move. I didn’t want to look like a coward but I trembled at the thought of going into that dark tunnel alone.

The man sighed, “It’s a grave, it’s where they buried it, long ago, and they built the chapel over it. But one of the masters got wind of that and tried to bring it back, then when that all went wrong, instead of blocking it in, they just built a trapdoor over the grave and threw away the key. Stupid, foolish thing to do. Your uncle must have found the spot, see how the door’s rotted clean away-” He pointed to the hole. I tried to digest the information he had rattled off at me.

“I don’t understand, what did they bury?” But the man just looked at me as if I was an idiot.

“Do you think my uncle might have fallen down there, is that what you’re saying?” I felt panic mounting, it was looking as if I might have to go down into the dark after all.

The man just pointed to hole, “see for yourself” he said, and handed me a little pack of matches. “For when you get to them,” he said, without optimism.

I got down on my knees and stared into it. I steeled myself and inched forward into the hole. The cloying smell of the earth was rancid, and the air in the tunnel, unusually warm. I pulled myself forward a little way, until I felt the passage begin to slope downwards. I called out my uncle’s name, but the earthen walls deadened the sound of my voice almost immediately. I scrambled along, my heart pounding, desperate to turn back, but compelled by pride and morbid curiosity to keep going.

My hands touched something cold. A stone floor. In that instant I could smell it, that cloying scent stronger, mixed with something foul. My hands shook as I tried to light a match but when the flame ignited I had to struggle not to blow it out. In front of me lay the bodies, a mess of bones and flesh atop a mound of collapsed rubble. I closed my eyes and clapped a hand to my mouth to keep from retching. When I opened my eyes again I saw the same scene of guts and spilled blood, and on the floor, line after line of carvings into the stone. They might have bee words, or just patterns, I only caught a glimpse of them, I can’t be sure what they were exactly, but they encircled the room. A few feet away from me the carvings were disturbed by a hole in the stone, a pick axe lay nearby. It looked relatively modern.

I scrambled out of that hole as fast as I could go backwards. I didn’t dare turn my back on that place. The man took hold of my legs and pulled me out onto the grass, his face pale and etched with concern.

I had no idea what to say to him, I couldn’t erase from my mind the image of those eviscerated bodies.

“Did you not know.” The man said, with pitying eyes. He produced something from his pocket and handed it to me, pointing to a page, on paper I recognised.

“That’s my wife’s handiwork. I gave the woman a copy when I saw her out here, hunting around, I thought it might help but they just laughed of course.”

I looked down at the pamphlet, the same as I had found in the bathroom. I realised that it had been in my jacket pocket since last night.

I brought it out to show him.

“Aah yes, that’s my writing there too,” he pointed to where the words had faded in the water.

“The missing letters, they should be B…A…R.”

The name came back to me, from stories of my youth of black dogs on the moors. I saw again the image on the book my uncle had sent me.

“Barguest.” I said, and the old man nodded.

“I saw the bodies, they were lying on broken stones.” I found it hard to tell him what I had just seen, but he appeared unsurprised, his weathered face long and forlorn.

“Broken stones,” he said, and tutted. “It’ll rise again. Have you had the dreams?”

I stared at him terrified, because I knew what he meant.

“Yes, yes a few times.”

His face grew even darker, “then you best be off. Sell the house, but before you do, send some men to fill in that hole. Cement, anything solid. I don’t know if it will make a difference but it might stop someone new from tampering with it. Your grandfather knew all about it from my father, that’s why he didn’t go poking around, you don’t want to risk the same happening to some other poor fool who thinks you can ignore these things.”

“What do I tell them police?” I asked.

“Not a damn thing.” He said, and he began to walk off. “You must never come back here, never, none of your family can.”

“But what if it’s not them?”

He motioned me to follow him, “what do you think,” I knew in my heart he was right, and that it was my uncle and that women who had been so brutally annihilated.

I followed him out of the copse, and I did as he said. I still have the dreams.